What It’s Like to Livestream a Funeral

Grace Druien is “kind of a professional funeral-thrower.”

The 27-year-old photographer from Holcomb, Illinois, has helped orchestrate end-of-life celebrations for many friends, family members, and people in her tight-knit community. But until her father died this month, she’d never livestreamed a funeral.

“We kind of had this rinky-dink thing set up,” Druien said. To get the phone camera angled above people’s heads, she balanced it on one of the funeral home’s floral arrangement stands. As the pastor stood to give his sermon, she and her sister pressed record on the Facebook Live video, and rushed to their seats up front. Outside in the funeral home parking lot, family members and friends watched the feed on their phones in their cars.

Druien isn’t the only person experimenting with digital funeral strategies. As coronavirus has spread around the world, it's left death and, paradoxically, cancelled funerals in its wake. To slow the spread of the disease, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told funeral directors on March 16 to livestream funerals when possible. No one yet knows how long the COVID-19 pathogen can survive on a dead body, but it’s clear that the living pose a threat to each other. Multiple coronavirus outbreaks around the world, from Spain to Albany, Georgia, began at funerals.

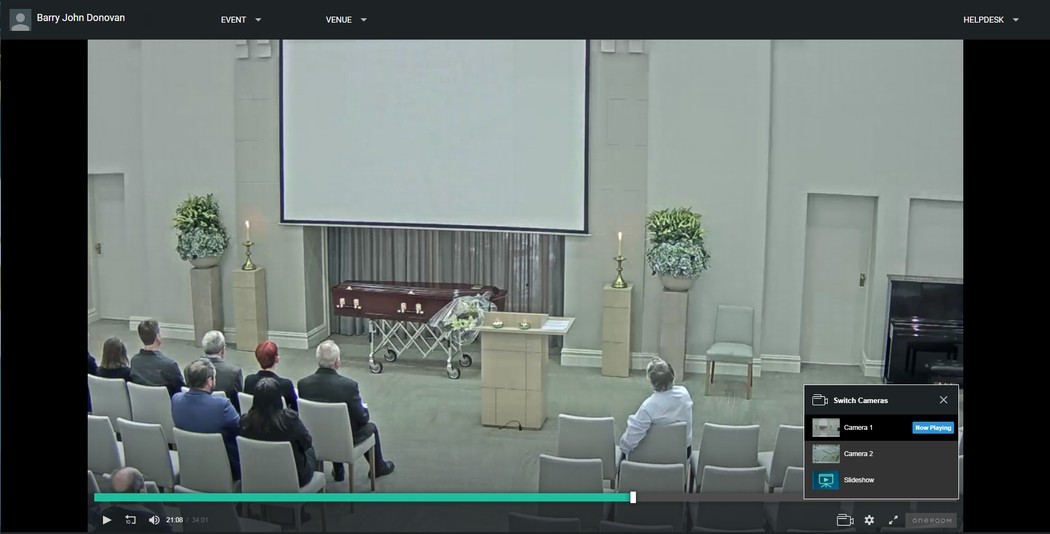

But the CDC’s mandate hasn’t been easy to follow. Only 20 percent of funeral homes offered livestreaming in 2019, according to Wired. “It was almost like a nice-to-have, but it just wasn’t really sinking in,” David Lutterman, the CEO of OneRoom, a funeral streaming start-up, told us. “With this [coronavirus] situation, it raced to the top of number one on everyone’s list in the space of a few days.” OneRoom is working to meet demand, but there’s only so many cameras they can install in a day. As companies play catch-up, morticians and mourners like Druien end up doing funeral streams themselves—with all the expected hiccups.

Druien’s dad died from mesothelioma on St. Patrick’s Day. It was the last night their local hospital allowed visitors. His funeral was held that Saturday, hours before the state of Illinois’ “shelter in place” law went into effect. Funeral homes were already barring gatherings of more than 10 people and restricting ceremonies to immediate family, so Druien decided to set up a livestream.

After they pressed record on the Facebook Live video and sat down, Druien realized she should probably check the livestream was working. When she looked on her own phone, she saw the video had no sound.

“I was like, ‘Oh noooooo,’” Druien said. “I nudged my sister and just kind of discretely showed her the phone and her eyes got real big and we both got up and ran back around.” They ended up restarting the stream. In the comments, Druien asked if there was sound this time around, and people immediately wrote back to confirm there was, including a childhood acquaintance who had since moved to Florida.

“That was kind of a surreal moment for me, because I realized people were watching it,” she said. “There were people who actually cared and were at home and instead of binge-watching Netflix, they’re taking time out of their day to watch my dad’s funeral.”

Other livestream issues haven’t been so easily resolved. One YouTube user asked friends to recruit new followers for him, so he could get over the 1,000-follower threshold required to livestream on the site. Even when you get your video online, it’s no guarantee others will be able to watch it. One Twitter user screenshotted the blacked-out screen of a friend’s YouTube livestream funeral. The unlisted video had been blocked by Warner Music Group, because the family played copyrighted music as part of the ceremony. And there are other downsides to these platforms, too. Funerals on YouTube are formatted like any other, with likes, dislikes, and the number of viewers prominently displayed beneath the video.

Laura, 23, recently tried to watch a friend’s funeral livestream. (She asked for her last name to be withheld to protect the family’s privacy.) “There were a couple seconds where it did go live and we did hear someone singing, but it was just about 3 or 4 seconds,” she said. For more than two hours, she waited for the single frozen frame of the family standing by the coffin to move. It never did.

“In my head, I was like, well, if I can’t attend in person, and at least I can say goodbye through a screen, and I couldn’t even do that,” she said. “It was a very hard day after that.”

When a livestream works, it can be a comfort to the family, said Daniel Ownby, a funeral director at Weaver Funeral Home in Bristol, Tennessee. It allows them to include people who live far away or can’t travel to participate. He’s tried livestreaming in the past at the family’s request, but working with Facebook Live or YouTube proved difficult. “You have a different problem every time,” he said.

In January, Ownby signed up for OneRoom, not realizing how prescient the choice would be. “It really worked out to be good timing,” he said. OneRoom’s team came and set up two cameras in the funeral home’s chapel: one at the back of the room, to show the officiant and the casket, and another at the front of the room, to show the people gathered for the ceremony. Now, all he has to do is schedule the time of the service in an accompanying app, and the cameras will roll automatically.

“We set it and pretty much forget it,” Ownby said.

People all over the world can watch the stream live, but families can also return to the recording later. “You don’t hear everything” in the ceremony, Ownby said, “so it’s been nice for them” to revisit.

OneRoom has been offering funeral livestreams since 2012. But the company, which started in New Zealand and serves about two-thirds of all New Zealand funeral homes, had a harder time breaking into the American market. They found success in some obvious places. “Where it fit really well is where there are funeral homes that are serving immigrant communities,” Lutterman, the CEO, said. But struggled to convince funeral directors that the sick and isolated would also want to attend.

But coronavirus is proving there’s more of a demand than many funeral directors anticipated. “It all went vertical,” Lutterman said. “Now it’s very tangible,” Lutterman said. “But the need was always there—it was there before and it will continue to be there afterwards.”

Druien sees funeral livestreams as a whole new world of possibility. “It’s never something I thought about before, [but] since my dad passed away, other people in my community have been passing away, and I can’t be there. And it’s horrible,” she said. “You can’t just pop up and ask” others to livestream their service for you, she added. But if people choose to, they should know “people you wouldn’t even think about caring care.”

Source: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/3a8m4k/what-its-like-to-livestream-a-funeral

.png)

.png)